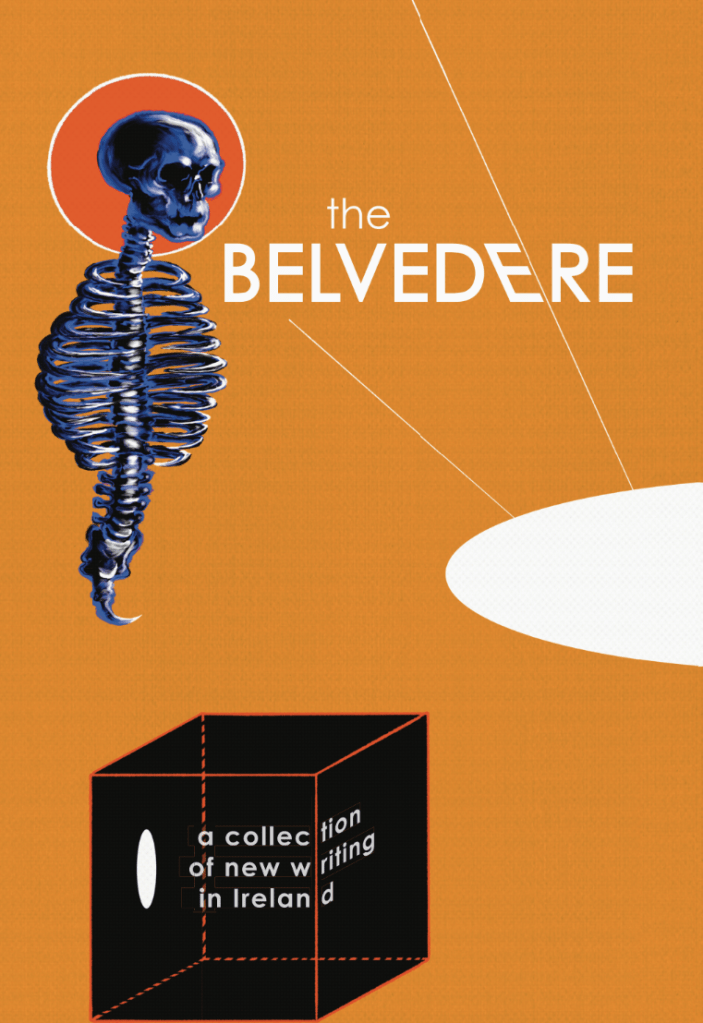

The Belvedere: Volume 1 is lucky enough to boast cover art by Day Magee, a Dublin-based artist whose work, in their own words, “concerns the grieving of futurity as per the subjectivity of a queer sick body—queerness navigated via fundamentalist Christianity, and illness as manifest in chronic pain. Taking the form of performative multimedia, from live performance to image-making, the written word and music, they manifest and chronicle a self-mythology.”

Day was named the DCU 2024 Visual Artist in Residence, among their many other accomplishments, and was thus one of the first people to be considered for cover artist. In the end, their evocative and gorgeous work simply fit the collection of writing being produced. The painting donated for use sets the tone of Volume 1—and, through that, the future of the journal.

To explore more about their career, Managing Editor Kasandra Ferguson sent Day some questions about their interests, their work, and their time at DCU. Also, the nuances of artist expression, queer identity, illness, God, and all those frivolous things.

12 August 2025

[KF]: You’ve produced visual art, performance art, and music, showing an affinity for a variety of mediums. How important is the use of all mediums available to you in creating and displaying your work? How does the experience of using your body in performances for an audience mimic the experience of interacting with others and creating a persona for day-to-day life?

[DM]: I would argue that I am the medium. These given processes (say, writing) and artefacts (say, a poem) and the contexts in which they locally (on a page) and otherwise (in a magazine) exist are enacted through me. I am the common denominator. They are all languages. It is less that I learn them (for I am too much of a generalist to know them as a master would), and more that I learn myself through them. They are nodes that compose the gestalt of me. I too am a node that compose another centre, and so on. Indeed, composition functions as the most universal medium, for it applies not simply across art but in the social and even the scientific: the relationship of parts to the whole and to other wholes, and how these relationships are arranged in different times and spaces.

[KF]: You’ve been displaying work in shows and exhibitions for the guts of a decade. How has it changed in that time? Do you feel your art constantly evolving, or do you find yourself very consistently centred on specific styles and motifs?

[DM]: I have changed. Inevitably, my relationship to art has also had to change—indeed, I believe right now in my life and practice to be a period of existential, constitutive transition for that relationship. As with any relationship, you must listen to what is being said and not what you would like to hear. This necessitates silence—silence not only to listen, but to actually leave; to not consciously figure it out, but to unconsciously allow creativity to unfold. It is conversational, with peaks, valleys, and all sorts of obstacles.

In a way, the artist is a living self-talk made public, the works being the statements that resonate. It is through such a process that other human beings may realise their own self-dialogue and what forms this self-dialogue may take. I often debate other artists as to what is and isn’t art, and I concede that the above speculations might render me less an artist than someone who lives creatively. Perhaps, for me, what we call “art” is but a means of creative, applied philosophy.

[KF]: You focus heavily not only on the impact our bodies make on our personal narratives about our place in the world, but also how said narratives continue to affect our self-image and evolution as an individual. How do you feel this concept interacts with both visual art and literature as mediums?

[DM]: To be transparently sentimental, I will quote The NeverEnding Story II (1990): “We are all part of a never-ending story.” As storytellers, as well as being tellings of a story or stories ourselves, we are habitually obsessed with narrative resolution. If, however, you venture out into the weeds of the mediums and their histories, you will find that their best examples frustrate resolutions if not clichés (without abandoning these entirely). This, I think, is because no one person, no one living story or telling, ever gets and thereby lives The Big Picture. An image, too, is a story—a thousand words, and all that. Both image and story are compositions—the infinitely alternating arrangement of elements in a given framework.

We are each curves, angles, and inclines in a greater pattern—and nor is that greater pattern necessarily equilateral or symmetrical, though we approximate as much in totalising (and thereby totalitarian) ideas like Sacred Geometry, which seek to equivocate everything under one structural rubric. This renders us each contingent, relegated to our time and space in this Big Picture. We can only see geocentrically from where we are as individual organisms. This is where faith comes in—indeed, faith in other people. We must think heliocentrically, beyond ourselves. We must believe that they exist beyond our preconceptions of what a story’s content and structure should be, whilst knowing that there is content and there is structure to them, however alike or unalike to ours theirs are, and that however tangentially, we are part of them.

[KF]: I come from a community of Christians in which some rely heavily on “faith healing,” trusting that any illness that God wants cured will be so. In your work, you discuss the overlap between a condemnation of queer identity and the implicit condemnation of those with chronic illness, positing both peoples as capable of reaching a higher state wherein they are free of both “afflictions.”

What are your feelings on how Judeo-Christian faith is often viewed as an avenue to purity or healing for the self—and what this purity or healing concerns—rather than as a basis for community and connection with others?

[DM]: I think this relates to an underlying sense that health is a virtue, and thereby virtuous or a mark of value. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, in a pharmacy, you’ll often see beauty products sold next to health products. I often think about the etymological link between “virtue” and “virtual”—which amounts materially as acting “as if,” which necessarily is an operative mechanic of living in faith. We all live in some kind of faith by virtue of not knowing the future. Part of how we approximate certainty in the face of this principle unknown is in the inherited knowledge of the healthy body.

This narrative is compelling because health relates to our mortality—death being the most fundamental manifestation of our uncertainty, something we all inherently relate to—and this translates meaningfully into who survives and who doesn’t. The problem is that these inherited narratives of what (or who) is healthy and what (or who) is not healthy excludes certain bodies via the writing of history. This illustrates what kinds of bodies get to survive (and indeed thrive), which exposes ideological imperatives in the writing of histories. Physical health is real and intuitive, [while] pain and symptoms are messages that something is not right, and we should not aspire to illness—but if you can’t accept that reality is multiplicitous and does not conform to historiography, then you are living in some kind of denial.

Religions—if not ideologies in general—socially and approximately constitute what we call a given “community.” All communities require exclusion so as to define and legitimate themselves, which necessitates denial—of other people, and of other ideas. Our nervous systems too necessarily must delegate their attention, filtering the vast wall-of-noise of sensory information they are perpetually faced with. We cannot possibly know everything, and so, overwhelmed, we must delegate—this process of delegation results in relegating and compartmentalising our experiences (of ideas as well as people) to certain narrative roles.

This imperfect process, of tooling together our limited experiences of what is separate from us, results in an organic mess of this-that-and-the-Other. In other words—a body. Communities, religious and otherwise, are bodies, organisms unto themselves that we compose. They each have distinct organs that, conceivably in a healthy state, communicate with one another well—and for each organ to know when to come forward and when to recede in ongoing, harmonic equilibrium. These bodies, like any, are afraid of dying, and this fear of death is reliably narrativised in predator-and-prey scenarios that they enact upon the world via what is different from them—Other communities. These social enactments satisfy a hostile picture of the world that is easier short-term to manage than one of interdependence, where we go beyond our own skin (whether literal or communal) and beneath another’s.

[KF]: An oft-cited aspect of oppression faced by queer people is the statistical fact that our life spans are shorter. Whether through violence, death by suicide, or other factors, members of the LGBTQ+ community don’t on average live as long as straight, cisgender people.

How does the use of this fact when advocating for queer rights relate to your experience as a person with chronic illness, especially following a global pandemic wherein the health and humanity of chronically ill people was often deprioritised?

[DM]: Time necessarily lives through alternating identities via bodies differently. By virtue not simply of our humanity, but of our being mutually alienated social organisms, we must come to terms with our fundamental separation from one another whilst reconciling our need for other human beings.

Ironically, part of this means departing from our desire for an individual and communal symbolic identity (recognising that symbolic identity is part of being human), and distinguishing it from our collective material needs (housing, healthcare, etc). If we are to assume and advocate for the authorship of identity through the individual and our given demographic community, we must take responsibility for this and live that authorship knowing its limitations. We must hold lightly to it whilst simultaneously advocating for its existence by ourselves existing. This is tricky when identitarian narratives are politically useful for identities, but also resourceful data for capitalist paradigms to absorb and socially deploy among the more general population, resulting in its own purposes of commodified, individualist atomisation.

This tension involves, for everyone, subaltern or not, living with paradox—with contradiction. We, not least as a society so historically matured with rationality, cannot literally internalise and live this, no matter how much intellectually we can conceive of it, and so this requires acceptance—a thankless self-reconciliation. Cultivating a space within us that is inviolate and yet porous, that we must foster in the face of oppression without hardening our hearts and numbing us further to other people.

[KF]: How do you learn from and contribute to the Irish visual arts scene, specifically? How do you feel you’ve been received here? What are your specific influences?

[DM]: I have been very lucky to move between numerous creative circles in the arts, not simply the Visual Arts. I think the precarity of subsisting in the Visual Arts lends itself to co-mingling with the other, more commercial ends of the arts spectrum. There is a structurally stochastic, sponge-like openness to the Visual Arts that renders it more porous, allowing us both to absorb from as well as leave our own idiosyncratic mark upon the other creative communities. This is born out of necessity (being the least commercially viable and thereby most in-explicit-need of a social network), but also form. As in, its increasing lack of form is what allows the Visual Artist to diversify.

In turn, my creative influences generally come outside of the Visual Arts. Music and theory tend to charge my creativity and its motivations. I’ve recently just emerged from a warren of the musician Joni Mitchell and theorists Darren Allen and Ernest Becker, as well as novelists Clarice Lispector and Richard Yates. I am currently fixated on mixing the soundtracks for Contact (1997) and Artificial Intelligence (2001) in randomised playlists, while also dipping in and out of Bruce Fink’s [A Clinical] Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis. The chief influences I find however, are in the brief, melodic resolutions one gets to find in life itself outside of art. The islands of love one either discovers or is shipwrecked upon.

In terms of how I’ve been received in Ireland, I don’t know what else to say other than that I’ve been blessed. I recently began a year-long live-in residency at Fire Station Artist Studios in Dublin City Centre. I’ve never had my own place before, nor such an extended period of time to create at my own pace. It is interesting, however, even with whatever success one can muster, to still arrive at one’s relationship with one’s self. I am however trying to lean into this, as part of a greater personal narrative—to reconcile one’s self with being alone. Typical human stuff, really.

[KF]: What did you find to be the most impactful aspect of your experience as a DCU Visual Artist in Residence?

[DM]: In my studio on All Hallow’s Campus, I wrote a novel. A novel about being an artist. Though I did compose visual and performance work during my residency here, in typically contrarian fashion my muse had other ideas. Perhaps someone reading this should reach out and help me publish it (forgive me—better to ask for forgiveness than permission, in terms of self-promotion). In any case, I will always remember this place as where I systematically realised a dream, and for that, I am grateful. For that, I will continue to write.

Learn more about Day on their website below and be sure to follow them on social media!

Leave a comment